- Mental Health Law Online (MHLO). MHLO is by far and away the most useful legal resource for mental health and mental capacity law on the net. It’s got everything: statutes, judgments (far more than BAILII for this area of law, and with a very helpful system of indexing by subject, case summaries, links to subsequent and antecedent judgments in the same case, links to any newspaper articles, blogs etc about a case, and even a list of cases with ‘missing’ judgments!), it’s got a glossary of technical terms, links to statistical resources and links to consultations. You can have MHLO send updates to you by email, or to your Kindle, you can pose your questions to a discussion list where you might find answers or a sympathetic ear, it’s got an in-house CPD scheme, job adverts, hell – it’s even got a bookshop. I fully expect this website to start serving me my morning coffee in the new year. The most amazing thing about MHLO is that it’s almost entirely the work of one man, Jonathan Wilson, leading open justice into a brave new digital future. To help cover the costs of running MHLO, you can make a donation (see homepage for details). I couldn’t have done half of my research without this website, long live MHLO! [Update! You can purchase now a very reasonably priced kindle or paperback version of MHLO's annual review for 2012.]

Eleanor Roosevelt, 1958

'Where, after all, do universal human rights begin? In small places, close to home -- so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any map of the world. Yet they are the world of the individual person... Unless these rights have meaning there, they have little meaning anywhere. Without concerted citizen action to uphold them close to home, we shall look in vain for progress in the larger world.' Eleanor Roosevelt, 1958

The Small Places has moved...

The Small Places has moved to a new home here, including all the old posts. Any posts after 6th March 2014 will appear on the new website, but old posts are preserved here so that URLs linking here continue to work. Please check out the new site.

Thursday 27 December 2012

My top ten Mental Capacity Act resources

Charlotte Emmett: The significance of capacity assessments for care and residence decisions

I am so pleased to be able to share this guest post by Charlotte Emmett, Senior Lecturer in Law at the University of Northumbria. Alongside Marie Poole, John Bond and Julian Hughes, Emmett recently published some research on capacity assessment which I would strongly urge everybody with an interest in the Mental Capacity Act to read (Homeward bound or bound for a home? Assessing the capacity of dementia patients to make decisions about hospital discharge: Comparing practice with legal standards.) Homeward Bound was an ethnographic study which pre-empted to a quite remarkable degree many of the problems identified by Baker J in the recent case CC v KK. The project was part of the Assessment of Capacity and Best Interests in Dementia Project at Newcastle University, headed by Julian Hughes and funded by the National Institute for Health Research. In this guest post, Emmett reflects on the significance of capacity assessments about care and residence decisions for older adults.

Every day, decisions are made to discharge older people with dementia from hospital into institutional care. These are often permanent moves. Sometimes they are made voluntarily and sometimes older people lack the mental capacity to express a choice and so health and social care professionals make these decisions for them in their best interests. Studies tell us that a significant number of older people may welcome a move from their own homes into a permanent institutional care, but this isn’t always the case; indeed, relocation can often be the last thing that an older person wants, especially when that person has dementia and declining mental functioning and is already experiencing the discontinuity and disconnect associated with the condition. They may resist the placement, verbally and physically. But they are relocated anyway.

Thursday 20 December 2012

DNAR's and the Mental Capacity Act 2005

This is less a blog post, more a brain splat. I apologise. I haven't got the time or mental energy to devote to a proper unpicking of the relationship between 'Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation' orders (or DNAR's for short) and the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA). So I'm just going to pose some questions that trouble me about a couple of recent DNAR cases, and leave them hanging in the air like a bad smell and then scarper.

Let's get the preliminaries out of the way shall we? DNAR's usually apply only to cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (hence DNACPR) although they can refer to other kinds of resuscitation (hence why I'm sticking with DNAR for the sake of generality). Just because there's a DNAR order, doesn't mean you'll be refused other life-sustaining treatments, like antibiotics or whatever. Resuscitation is obviously a form of medical treatment, and as doctors incessantly remind us it's nowhere near as effective as it's portrayed on TV. If it's not effective, you've lost your chance to peacefully slip away, as the odds are you'll die on a gurney with a doctor breaking your ribs. Furthermore, if a person is starved of oxygen for a significant duration there are significant odds of brain damage, sometimes extremely severe brain damage.

But, on the other hand, for people who are determined to live, those are odds worth taking.

Three recent DNAR cases

Wednesday 12 December 2012

Thought provoking papers on capacity

I came across two fascinating papers this week that I thought I'd share, both of which have interesting implications for that slippery concept we call "mental capacity". The first was a case report by a medical team who had 'established capacity'* in a patient with partial locked in syndrome (Carrington, S. & Birns, J. (2012) 'Establishing capacity in a patient with incomplete locked-in syndrome', Progress in Neurology and Psychiatry 16(6) p 18-20 - happily the paper is FREE!). This is one of the first papers I've seen on the communication aspect of mental capacity. As Tom O'Shea and I were pondering on Twitter, I wonder if this test would have come out differently if the man had been making decisions which his treating team disagreed with. The paper is also of interest in connection with advance decisions, because whereas before his stroke the man had indicated he would not have wanted to live with partial locked-in syndrome, following his stroke he not only wanted life-sustaining treatment, but he wanted to be resuscitated in the event of cardiac failure. A lot of the debates surrounding Tony Nicklinson's request for assisted suicide assumed that nobody would want to live in his shoes (yes Polly Toynbee, I am talking about your particularly offensive article), yet a survey conducted last year actually found that a majority of people with locked in syndrome were happy and only a minority wanted to end their lives. The point (for me) about Nicklinson was about his autonomy to do something non-disabled people would be able to do independently. We should approach with extreme caution the assumptions people who haven't experienced a condition first hand make about quality of life. This, of course, has a bearing on the ongoing DNAR debates, but that's another post for another day.

Thursday 6 December 2012

DoLS v Guardianship - redux

It says a lot about the readers of this blog, that one of the most popular posts I've written is an interminably long, three-post, technical discussion of whether guardianship under the Mental Health Act 1983 would be preferable for safeguarding the human rights of people deprived of their liberty than the Mental Capacity Act 2005. The original posts can be found here, but they are getting a bit creaky and out of date and contained some inaccuracies. So, given the debates around whether DOLS need replacement are still alive and kicking, I present to you: DoLS v Guardianship - redux (if you can't download that, drop me an email). Here's the summary:

Monday 26 November 2012

Improving Enforcement in Adult Care Homes

Another week, another consultation. The Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (DBIS) are holding a review of regulatory enforcement in the adult social care sector. The website says:

In this review, we are asking anyone involved or interested in the adult care home sector to let us know their views and experiences on how current enforcement of regulation in this sector is working. This is part of an initiative to drive up standards and enable providers to achieve the highest standards of care, while removing confusing bureaucratic requirements that divert carers from meeting the needs of residents.

Pigs in clover

I am happy as a pig in clover this morning, as those lovely folks at Emerald Journals let me have a peek at the latest edition of The Journal of Adult Protection, which is entirely given over to discussing the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA).

Friday 23 November 2012

Like water dripping on stone

|

| Image by Hans |

Tuesday 13 November 2012

Liberty call for overarching inquiry into the adequacy of safeguards under the Mental Capacity Act 2005

A while back I had a little whinge about how few disability and human rights NGO's were campaigning about the paucity of safeguards under the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA) and the shocking problems with the deprivation of liberty safeguards (DOLS) in particular. Behind the scenes, I think there is growing concern about the MCA and the risk of unchecked decision making powers it affords under the 'general authority' (now called the 'general defence'). I only just spotted this, so apologies for the delayed response, but Liberty have written to the Joint Committee on Human Rights and called upon them to open an 'overarching inquiry' into the MCA - and in particular to its paucity of safeguards. They have also drawn attention to the direction of travel of DOLS case law, and expressed concern at the narrowing of the definition of deprivation of liberty. I fervently hope that the JCHR will consider taking up this call, and would encourage other individuals and organisations who are concerned about the inadequacy of safeguards for decisions made under the MCA and the serious problems with the DoLS to consider writing letters in support of Liberty's proposal.

Monday 12 November 2012

We were right to be worried about Worcestershire

I'm afraid this is a rather short, but depressing, post to bring to your attention the decision of Worcestershire County Council to pass its maximum expenditure policy (MEP). I wrote about the policy previously here, the grass roots Spartacus campaign produced a report on the proposal called Past Caring, available here. Following the publication of Past Caring Worcestershire decided to extend the consultation, and information which the report criticised Worcestershire for not putting on the consultation website was subsequently added.* Worcestershire's response to Past Caring does not address the concerns about human rights at all, although it's recent cabinet documents (here) state that they see no conflict with Article 8 (Article 5 is simply not discussed). The response also says that the Council will provide more details on what 'exceptional circumstances' it will depart from the policy in, but I can't see anything on the consultation portal which mentions this. I've tried to find this policy for older adults online elsewhere on their website, but with no success, so we're still none the wiser as to what kinds of exceptional circumstances WCC might increase expenditure above the value of a residential care placement. In any case, this information was not presented as part of the consultation.

Friday 9 November 2012

The Great Escape (a schematic)

Greetings from deepest, darkest, thesis land. I am in the thick of "writing up", and barely have time to get dressed let alone write a blog post. But here is small offering in lieu of a proper post - an attempt to schematise how you might try to get out of detention using Schedule A1 of the Mental Capacity Act, otherwise known as the dreaded DOLS (Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards). It includes a few other regulations and bits and bobs that tie up some (but not all) of the loose ends in the Great Escape. Obviously my reasons for posting it here are entirely selfish - this figure (or a jiggled around version of it) will be going in the thesis as an appendix, so if you spot any mistakes please let me know! You can download the pdf from here.

Wednesday 31 October 2012

Parliamentary debate on Court of Protection appointed deputies

I would strongly recommend readers take note of a recent parliamentary debate on deputies appointed by the Court of Protection, triggered by Duncan Hames MP (Liberal Democrat, Chippenham). The debate can be found here (about halfway down the page, column 53). Mr Hames details a story of his constituent "Mr Able". Mr Able was appointed a solicitor as a deputy to manage his finances after he received a compensation award. Within nine years that award was wiped out, and much was spent on paying the deputy himself and on fruitless litigation on other matters. Hames comments:

'More than a third of the personal capital that Mr Able possessed when control of his financial affairs was passed to court-appointed solicitors was subsequently paid to those solicitors as fees for the job of controlling his expenditure, yet they did not even ensure that he received appropriate benefits when he was unemployed. 'More alarming was Mr Hames' description of the monitoring arrangements on the activity of the deputy. The Court of Protection visitors stopped visiting Mr Able in 2003, and he did not receive another visit until 2011 - despite his funds being wiped out and a change of deputy when eventually the local authority took over. In 2009 when Mr Able's first deputy (the solicitor) applied to be discharged, the Court of Protection visitor wrote a report on Mr Able without having even met him. Duncan Hames MP contended 'that not having Mr Able visited at any time in eight years demonstrates a terrible sense of complacency among those who were meant to be looking after his best interests.'

Monday 22 October 2012

Mood Mate

I get quite a few emails asking me to promote apps and gadgets and products on the blog, which I send straight to my recycle bin, but since this one is not seeking to make money out of anybody and might actually be useful to some readers I said I'd post it here.

Alexander Gyani is a PhD researcher at Reading University, and he's made an iPhone app to help people locate local non-medical treatments for common mental health problems like anxiety and depression. Apparently it will signpost people to Improving Access to Psychological Therapies services. The app is called Mood Mate, and it is part of a research project to 'help researchers at the University of Reading find out how to help people with anxiety and depression find local treatments and hopefully change their lives for the better'. You can find out more about the research and download the app from here. Any questions - ask Alex not me!

Alexander Gyani is a PhD researcher at Reading University, and he's made an iPhone app to help people locate local non-medical treatments for common mental health problems like anxiety and depression. Apparently it will signpost people to Improving Access to Psychological Therapies services. The app is called Mood Mate, and it is part of a research project to 'help researchers at the University of Reading find out how to help people with anxiety and depression find local treatments and hopefully change their lives for the better'. You can find out more about the research and download the app from here. Any questions - ask Alex not me!

Friday 19 October 2012

Thank goodness for Strasbourg: Kędzior v Poland

So, to recap, the courts started out reasonably well and gave analyses of deprivation of liberty which accorded with common sense (e.g. JE v DE, 2006; G v E, 2010). Things started to go weird in MIG & MEG, where apparently not being free to leave a place no longer had any bearing on whether or not you were deprived of your liberty. In P & Q the Court of Appeal confirmed that you probably weren't deprived of your liberty unless you were objecting to your confinement or the place you were in did not satisfy a judge's idea of 'normal'. Being drugged with powerful sedating anti-psychotics might be a factor, but having noted that the Court of Appeal didn't deign to explain why it wasn't in that particular case. In Cheshire we learned that the 'normality' against which deprivation of liberty should be assessed wasn't the normality of the man on the Clapham Omnibous, it was - to paraphrase - the normality of "people like that". By this point it became clear that a care provider would have to recognise they were subjecting a person to a degree of coercion which was an excessive response to a person's impairment in order to give them any safeguards against excessive and unlawful coercion. I'm sure care providers are falling over themselves to acknowledge that their care is more restrictive than it needs to be. But Cheshire did at least give you a get out if you had another place to go to (paragraph 58). Except that only a month later in Re RK a girl who was miserable in her care home, whose family would have offered her a place to live if the local authority would stump up a decent care plan to support them, was found not to be deprived of her liberty. And then the foreseeable but indefensible descent to C v Blackburn with Darwen - where a man who hammered down the door of his care home trying to escape was found not to be deprived of his liberty because he had nowhere else to go, and CC v KK where a woman who was both objecting and had somewhere else to go was found not to be deprived of her liberty because her objections did not give rise to a 'significant degree of conflict'.

So where are we now? In order to be deprived of your liberty in a care home of England or Wales you must a) have another place where you could go to, and b) must be objecting sufficiently to give rise to a significant degree of conflict. If you're reliant on the state to provide you with accommodation, if your family don't want you back, if your home was sold to pay for your confinement in a place where you don't want to live, if you're unable to communicate, if you're too scared to voice your objections, or if you do so but only politely, you are - apparently - at liberty. If you are subject to round the clock supervision and control, if you are not free to leave the place where you are confined to - temporarily or permanently, if you are drugged so that you cannot express objections, if you are subject to frequent physical restraint, if you are so institutionalised you've given up trying to get away, it is quite possible that you are actually enjoying what passes for a state of liberty in England and Wales.

Well, thank goodness for Strasbourg.

Monday 15 October 2012

Social work in the Other Europe

On my way out of the house I realised I had nothing to read for a long journey by rail and air. I grabbed the first book that I could find that would fit in my bag. My copy of The Case Worker, by György Konrád (1969) is a rather battered edition by Penguin, from a series called 'Writers from the Other Europe'. It's no longer in print, although you can buy it for a penny on Amazon. Of course, that Other Europe is long gone now, and Konrád's case worker has no precise parallel in the UK. The closest analogy to a case worker in 1960's Budapest might be a social worker with a hefty measure of benefits administration thrown into the mix. The book is based on Konrád's own experiences in such a role.

I'm afraid all this travelling has left me barely capable of stringing sentences together, but it's fascinating to see the way that Konrád's case worker's role is so imbued with the political and economic logics of that particular time and place. What is possible, and consequently what is acceptable, is defined by the alternatives on offer. And the framing of the very purpose of the case worker's role - 'to protect children and safeguard the interests of the state' - sounds so similar, and yet so different, to how social work roles would be framed in the UK today. The story of the Bandulas is shocking by contrast with the threshold conditions for child protection we operate in the UK today, but the case workers' decision has to be understood by comparison with the institutional alternatives on offer. And yet, for all the differences, there is something recognisably familiar about Konrád's case worker; his recounting of the power dynamics between case worker and client, his human responses to suffering, and perhaps sometimes also elements of his despair at the system he works within.

Friday 28 September 2012

A serendipitous judgment

If a judgment can be serendipitous, then this was. Last week I gave a case law update to the fantastic Yorkshire and Humber Best Interests Assessors conference. In that update I talked about Article 8 and issues where an older person wanted to return home, but it was felt they were safer in residential care. I described case law where the focus had been on a person’s desire to be reuinited with a loved one (in particular, DJ Eldergill’s judgment in A London Local Authority v JH & Anor [2011]), but grumbled that no judgments had yet been published about a person’s desire to be reunited with their home. This surprised me, as there are surely large numbers of older people in care homes who want to return to their homes, but where the ‘family life’ pull isn’t a factor. I then spent the best part of this week complaining about how fuzzy the concept of 'capacity' is, how little detailed guidance (as opposed to equivocal platitudes) the courts have given on how capacity should be assessed, and how much potential for arbitrariness there is in capacity assessments... So, it was with a great deal of pleasure that Baker J’s judgment in CC v KK and STCC (2012) arrived in my inbox this morning. In the first place, it’s a much needed case about an older person who wants to return home. In the second place, it goes into considerable detail about what a good capacity assessment looks like. This case will not only shore up people’s rights to self-determination, it should also place capacity assessors on a much surer footing about what is expected of them by the law. (By the by it also talks about the meaning of deprivation of liberty, and - with a few sideswipes at Cheshire - finds that a person who is objecting and 'has somewhere else to go and wants to live there' - see Cheshire [58] - isn't deprived of their liberty because their objections aren't causing enough conflict. But we'll let discussion of the parlous state of DOLS case law pass for now...).

Sunday 16 September 2012

The problem of domination in social care

On his blog today, parent carer Mark Neary described a series of occasions over the past couple of years where some element of support he and his son Steven receive from his local authority has suddenly been withdrawn, and then eventually reinstated without any real explanation. These are decisions with potentially huge repercussions for them, the most recent of which was to stop their housing benefit, which would potentially have had the effect of splitting the family up (again) and rendering Mark himself homeless. Within a month. Horrified, bloggers and journalists including Anna Raccoon, Billy Kenber at the Times and the Radio London breakfast show covered this latest sting in the tail of a story that began with Hillingdon unlawfully depriving Steven of his liberty for almost a year. Mark’s fab solicitor got in touch. And then suddenly, whilst describing what had happened on the Radio London breakfast show, the local authority’s director of social care and housing stated (on air) that they had personally intervened and reinstated the housing benefit pending further discussions. Mark writes:

In less than 48 hours, I swung from terrible despair and fear to triumphant relief and for what? If anyone from the social care field is reading this post, I would genuinely be interested in your theories of how things can change so dramatically, and so suddenly.I don’t have a theory which can account for what happened in Mark’s particular case, but I do have a theory of why these types of scenarios occur in social care with greater frequency than one might hope. It’s called the problem of domination. [Edit: 14/11/2012: see Mark's response to this post here]

Friday 14 September 2012

Mental capacity and voting rights

A discussion about care homes refusing to enter residents on the electoral register on grounds that they lack mental capacity to vote on the (brilliant) Mental Health Law Online discussion list prompted me to jot down a few reminders about mental capacity and voting rights.

Is mental incapacity a reason not to put a person on the electoral register?

No. And failure to provide information to registration officers about a person who is eligible to be on the electoral register may be an offence.

Is mental incapacity a reason not to put a person on the electoral register?

No. And failure to provide information to registration officers about a person who is eligible to be on the electoral register may be an offence.

Monday 10 September 2012

CQC, strategy and inspection frequency

There have been a lot of changes over the last year at CQC. Chief Executive Cynthia Bower has been replaced by former social worker David Behan, and Chair of the Board Jo Williams resigned last week. Although there are likely to be bumps in the road in the near future - notably the registration of 8,500 GP practices and the findings of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry in October - some detect change in the air, a regulator turning over a new leaf. CQC are currently consulting on their strategy for 2013-16, and one source of contention is likely to be the tricky matter of inspection frequency. I have previously written about the shift towards 'risk responsive regulation', an idea emerging from the Hampton Report and which resulted in the removal of a requirement for biannual inspections in care services in around 2007. Under CQC there is no statutory inspection frequency, but last year in interviews amid the fallout from Winterbourne View and uncomfortable witness testimony at the Mid Staffordshire Inquiry Cynthia Bower appeared to commit the CQC to doubling inspection frequency, perhaps to annual inspections (e.g. Community Care, HSJ). In 2010/11, inspection frequencies sank to an all time low - including, according to data CQC shared with me, an inspection rate of only 6% for learning disability services. However, CQC recently shared with me updated, data, shown in the graphs below, which shows that in 2011/12 they have worked extremely hard to increase inspection frequencies, with around 72% of all residential care services being inspected that year. This is really encouraging, the charts below speak for themselves of the effort that must have gone into increasing the volume of inspections. However, in CQC's recent strategy consultation and statements from David Behan, there are ominous signs of a U-Turn back towards risk based regulation - that is to say, removal or reduction of minimum inspection frequency targets, based on risk.

Thursday 6 September 2012

The conference season

The conference season is upon us, and there are some great conferences coming up on the Mental Capacity Act 2005, the Mental Health Act and the deprivation of liberty safeguards. Here's a selection, but if you know of others then please do send details my way and I'll post them here. I am attending a few of these. Where others drool over seeing their favourite bands in music festivals, I am quite beside myself with excitement about some of the talks, workshops and speakers that are lined up on the MCA and the DoLS... If you know of other conferences, seminars or events that might be of interest to readers, then drop me a line.

Tuesday 21 August 2012

The state isn't always better, but profit usually makes things worse

In the wake of Winterbourne View we are all looking for answers to the questions: How did this happen? How can we prevent it from happening again? There are as many different answers to this question as there are different responders. But there are difficulties with any one size fits all answer. It's easy to blame it on the regulatory model, but as the Serious Case Review (SCR) showed CQC was one agency among many which failed to respond adequately to whistleblower allegations. We could blame it on the model of care, and it was a vile model of care - storage, not support, as Neil Crowther put it. But abuse happens in community based care homes and supported living settings as well. Another pattern, which I want to discuss today, is to blame it on the privatisation of health and social care services.

Thursday 9 August 2012

DoL or No-DoL?

[Update! Check out 39 Essex St barrister Neil Allen's guide to 'Restriction on liberty or deprivation of liberty', which he's kindly said I can post here]

I have made a map to help you find your way through the labyrinth of Court of Protection and Court of Appeal rulings on the meaning of deprivation of liberty. Actually, you'll probably just find yourself going around in circles - take a piece of string, and watch out for Minotaurs! Enjoy - and let me know if you spot any mistakes. All the hyperlinks should link to the judgments, and the cases in bold are unlawful detentions. You can download a pdf copy from here, or a powerpoint slide here.

(I know. I need to get a life.)

I have made a map to help you find your way through the labyrinth of Court of Protection and Court of Appeal rulings on the meaning of deprivation of liberty. Actually, you'll probably just find yourself going around in circles - take a piece of string, and watch out for Minotaurs! Enjoy - and let me know if you spot any mistakes. All the hyperlinks should link to the judgments, and the cases in bold are unlawful detentions. You can download a pdf copy from here, or a powerpoint slide here.

(I know. I need to get a life.)

Wednesday 8 August 2012

Winterbourne

On Friday, the last member of staff from Winterbourne View hospital in Bristol charged with ill-treatment or neglect under the Mental Health Act 1983 (MHA) pleaded guilty. I had planned to go to court to watch the trial, but in the event the victims and their families were saved the additional pain of the evidence being picked through and watching efforts to defend the indefensible. This last defendant, Michael Ezenagu, is shown in the Panorama footage twisting a patient's wrists and fingers behind her back as she sits on the sofa, not threatening herself or anyone. Later on he says 'she’s a nice girl you know, but when she’s in a bad mood the only language she understands is force.' And until last Friday, he was going to plead not guilty to ill-treatment. It is hard to fathom what, precisely, he thought this footage showed, even now, even after over fifteen months to think about it.

With no trial, the reports on Winterbourne View that had been delayed so as not to prejudice a jury came tumbling out. Mencap and the Challenging Behaviour Foundation produced a report, Out of Sight, which drew heavily from the experiences of families of the Winterbourne abuse victims and those in similar situations. Although it wasn't written in connection with Winterbourne View, it's worth connecting their evidence of an absence of alternative services to this report by the National Development Team for Inclusion on why these services still exist, despite their huge cost, poor outcomes, and being discredited by policymakers, academics and campaigners. The Care Quality Commission produced their internal management review of regulatory involvement and failings in Winterbourne View - it appears, like their recent report on the learning disability services inspection program, to have been written in regulatorese. Much ink has been spilled about the CQC's new 'whisper softly but carry a big stick' approach; the Out of Sight report complains about the linguistic shift that came with the creation of the CQC:

With no trial, the reports on Winterbourne View that had been delayed so as not to prejudice a jury came tumbling out. Mencap and the Challenging Behaviour Foundation produced a report, Out of Sight, which drew heavily from the experiences of families of the Winterbourne abuse victims and those in similar situations. Although it wasn't written in connection with Winterbourne View, it's worth connecting their evidence of an absence of alternative services to this report by the National Development Team for Inclusion on why these services still exist, despite their huge cost, poor outcomes, and being discredited by policymakers, academics and campaigners. The Care Quality Commission produced their internal management review of regulatory involvement and failings in Winterbourne View - it appears, like their recent report on the learning disability services inspection program, to have been written in regulatorese. Much ink has been spilled about the CQC's new 'whisper softly but carry a big stick' approach; the Out of Sight report complains about the linguistic shift that came with the creation of the CQC:

Tuesday 7 August 2012

Allan Norman: Corollaries of the Right to Life: A Duty to Live or a Right to Die?

It's a pleasure to host this carefully argued guest post by solicitor and social worker Allan Norman on two important Court of Protection rulings on the 'right to die'. Allan takes up issues around the presumption of capacity, personal autonomy, quality v quantity of life, and the controversial question of whether resources should have a bearing on these decisions. If anybody would like to respond to Allan's arguments or arguments elsewhere on these cases, please use the comments below or get in touch if you'd like to write a guest post.Re E (Medical treatment: Anorexia) (Rev 1) [2012] EWHC 1639 (COP) (15 June 2012)

Thou shalt not kill, but need not strive

Officiously to keep alive

- from The Latest Decalogue, by Arthur Hugh Clough

A British Medical Journal editorial last month argued, 'Sanctity of life law has gone too far'. The Emeritus Professor of Medical Ethics, Raanan Gillon was specifically critiquing a judgement of the Court of Protection last year, W v M and Others [2011] EWHC 2443 (COP) (28 September 2011). That case held, notwithstanding the previously expressed wishes of the person concerned, who was in a minimally conscious state, that it was in their best interests to be kept alive, and that it was properly a matter for the court to decide. Gillon's editorial criticises the approach taken to best interests that overrides express wishes, the requirement to involve the court in best interests decision making, and the resource implications. The editorial has itself been criticised, as the UK Human Rights Blog has highlighted, as a call to "dehydrate dementia patients to save money". And that critique of Gillon resonates with another recent media story from another prominent health professor about the Liverpool Care Pathway, 'Elderly patients 'helped to die to free up beds', warns doctor'. With raw nerve criticisms like that, I am staking a lot when I defend Gillon's arguments, as I do here.

Monday 6 August 2012

Should we be using 'special' offences for crimes against disabled people?

Imagine a person came into your home uninvited, threw cold water over you to get you out of bed, forcibly gave you a cold shower, locked you in your room and tied your arms to a wheelchair so that you couldn’t move them, or out of the chair, for 16 hours. Would you consider that you had been the victim of a crime? Battery and false imprisonment, perhaps? Imagine somebody removed you from your home without any lawful authority, and you were locked in another place away from those you loved, unable to escape. Have you been kidnapped? Should somebody call the police?

These things happen in care, they aren’t common – but they aren’t especially infrequent either. We know they happen because they are detailed in regulatory reports, in civil law proceedings. But what struck me recently was how rarely the police are involved in these types of situations, and how rarely criminal charges are brought. I began thinking about this because I’ve been looking into the background of the criminal offence of ill-treatment or wilful neglect of a person who lacks capacity, introduced by s44 Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA), itself modelled on the offence under s127 Mental Health Act 1983 (MHA). Section 44 MCA is not unproblematic from the perspective of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), where there is a general preference for promoting and protecting disabled peoples’ rights through making mainstream mechanisms more accessible and inclusive, rather than developing separate systems for rights protection (e.g. Inclusion Europe, European Disability Forum). Even setting aside the complex and contested questions as to whether the label ‘incapacity’ is even compatible with the CRPD, the question is: why is an additional offence of ill-treatment or neglect of a person who lacks capacity needed, rather than making mainstream criminal offences more ‘inclusive’ and ‘accessible’ to disabled victims? I’m no criminal lawyer, but the more I looked into this, the harder it seemed to be to explain from any legal perspective why mainstream offences could not be used, and are so rarely investigated, in the context of care.

These things happen in care, they aren’t common – but they aren’t especially infrequent either. We know they happen because they are detailed in regulatory reports, in civil law proceedings. But what struck me recently was how rarely the police are involved in these types of situations, and how rarely criminal charges are brought. I began thinking about this because I’ve been looking into the background of the criminal offence of ill-treatment or wilful neglect of a person who lacks capacity, introduced by s44 Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA), itself modelled on the offence under s127 Mental Health Act 1983 (MHA). Section 44 MCA is not unproblematic from the perspective of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), where there is a general preference for promoting and protecting disabled peoples’ rights through making mainstream mechanisms more accessible and inclusive, rather than developing separate systems for rights protection (e.g. Inclusion Europe, European Disability Forum). Even setting aside the complex and contested questions as to whether the label ‘incapacity’ is even compatible with the CRPD, the question is: why is an additional offence of ill-treatment or neglect of a person who lacks capacity needed, rather than making mainstream criminal offences more ‘inclusive’ and ‘accessible’ to disabled victims? I’m no criminal lawyer, but the more I looked into this, the harder it seemed to be to explain from any legal perspective why mainstream offences could not be used, and are so rarely investigated, in the context of care.

Wednesday 1 August 2012

Interesting articles on capacity and deprivation of liberty

There are several brilliant pieces of writing about mental capacity and deprivation of liberty readers might be interested in.

The first is a blog post by Mark Neary relating 'a complete work of fiction' which describes the difficulty a person may have in challenging a detention if it isn't authorised under the DoLS. The problem is that often authorisation is never sought by managing authorities, or it might be sought but later on revoked because the supervisory body decide it's not actually a deprivation of liberty because the person has nowhere else to go, or their assessors hadn't heard the person object - even though everybody else has, or because the restrictions are 'necessary', or whatnot (assisted, no doubt, by the high level of uncertainty and contradiction in Article 5 case law). Without a DoLS authorisation there's no more advocacy rights, no more legal aid, no more permission-free routes to the Court of Protection to challenge it. So getting there requires a huge level of determination and awareness of the legal process, not to mention a hefty injection of your own cash - which you might never see again because of the general rule on costs in the Court of Protection. Basically, there's a technical right to challenge this "non-detention", but it's pretty inaccessible and comes with a huge price tag. Cynical supervisory bodies could revoke DoLS authorisations as a particularly sneaky chess move where litigation looks likely, and those deprived of the safeguards will struggle to have recourse against this. And as Mark points out - and particularly for older people - sometimes by the time these cases actually get heard, a person may have been detained for so long that the odds are stacked against them being released from detention to return home due to skills lost to institutionalisation, declines in health or even homes sold to pay for care or lost tenancies. Frankly some certainty as to the scope of Article 5, to help detainees and their supporters argue forcibly that the DoLS should apply, cannot come soon enough. In the longer term, the whole approach will have to be rethought.

The first is a blog post by Mark Neary relating 'a complete work of fiction' which describes the difficulty a person may have in challenging a detention if it isn't authorised under the DoLS. The problem is that often authorisation is never sought by managing authorities, or it might be sought but later on revoked because the supervisory body decide it's not actually a deprivation of liberty because the person has nowhere else to go, or their assessors hadn't heard the person object - even though everybody else has, or because the restrictions are 'necessary', or whatnot (assisted, no doubt, by the high level of uncertainty and contradiction in Article 5 case law). Without a DoLS authorisation there's no more advocacy rights, no more legal aid, no more permission-free routes to the Court of Protection to challenge it. So getting there requires a huge level of determination and awareness of the legal process, not to mention a hefty injection of your own cash - which you might never see again because of the general rule on costs in the Court of Protection. Basically, there's a technical right to challenge this "non-detention", but it's pretty inaccessible and comes with a huge price tag. Cynical supervisory bodies could revoke DoLS authorisations as a particularly sneaky chess move where litigation looks likely, and those deprived of the safeguards will struggle to have recourse against this. And as Mark points out - and particularly for older people - sometimes by the time these cases actually get heard, a person may have been detained for so long that the odds are stacked against them being released from detention to return home due to skills lost to institutionalisation, declines in health or even homes sold to pay for care or lost tenancies. Frankly some certainty as to the scope of Article 5, to help detainees and their supporters argue forcibly that the DoLS should apply, cannot come soon enough. In the longer term, the whole approach will have to be rethought.

Friday 27 July 2012

Some good news, some interesting news, and an appeal for information!

In case you haven't already visited the University of Nottingham's Mental Health and Capacity Law blog, can I point you towards two great blog posts on two great ECtHR rulings. The first is X v Finland, a case concerning the application of Article 8 ECHR to forced treatment. The ruling found that because forced treatment was an interference with a person's Article 8 rights, 'the domestic law must provide some protection to the individual against arbitrary interference with his or her rights under Article 8' [217]. The court was particularly concerned that 'the applicant did not have any remedy available whereby she could require a court to rule on the lawfulness, including proportionality, of the forced administration of medication and to have it discontinued' [220]. Over at the Mental Health and Capacity Law Blog it is suggested that this may have repercussions for compulsory treatment under the Mental Health Act 1983, because although we have - on paper - Wilkinson hearings, 'It is difficult to see that Wilkinson offers the sort of serious and practical legal challenge to involuntary treatment that the court in X would seem to want.'

Tuesday 24 July 2012

Lindsey Pike: Safeguarding adults and the social care White Paper

I'm delighted to host this post on safeguarding adults and the social care white paper by Lindsey Pike. Lindsey was recently awarded a doctorate by the Plymouth University for her research on maximising the effectiveness of safeguarding training in adult social care. Lindsey now works as a research and development officer at Research in Practice for Adults in Dartington.One of the 6 principles underpinning the approach in the social care White Paper is that

“People are treated with dignity and respect, and are safe from abuse and neglect; everybody must work to make this happen”.Some thoughts relating to are outlined below.

Tuesday 17 July 2012

The Cheshire effect?

Just a quick one to draw your attention to the two latest official reports on the deprivation of liberty safeguards (DoLS).

The first is the third annual report on the DoLS, published by the NHS Information Centre. The report indicates that DoLS applications continued their year on year rise in the third year, contrary to the predictions of the impact assessment. The impact assessment predicted that the number of authorisations would fall year on year, but that was predicated on the assumption that the DoLS would be applied to 21,000 people in the first year - when in reality there were only 7,157. Even in their third year, there were only 11,393 applications.

The first is the third annual report on the DoLS, published by the NHS Information Centre. The report indicates that DoLS applications continued their year on year rise in the third year, contrary to the predictions of the impact assessment. The impact assessment predicted that the number of authorisations would fall year on year, but that was predicated on the assumption that the DoLS would be applied to 21,000 people in the first year - when in reality there were only 7,157. Even in their third year, there were only 11,393 applications.

Thursday 12 July 2012

Spartacus: Why you should be worried about Worcestershire

Worcestershire County Council are consulting on a policy to cap adult social care expenditure at the cost of a care home placement. This will force thousands of care service users to choose between living with unmet care needs, or moving out of their homes and into an institution. Worcestershire's consultation is scant on detail, it does not discuss the savings it proposes to make and it does not explain how it will address the huge equality and human rights issues raised by this policy. This policy, if passed, would set a very worrying precedent for the rest of the country. The Spartacus Campaign have produced a report, a summary report and a blog post expressing their concerns. You can respond to the consultation here.Worcestershire County Council (WCC) are consulting on a policy to cap the maximum cost it will spend on care services at the cost of placing a person in a care home. If you feel bothered by this proposal, it would be great if you respond to Worcestershire's consultation on it, and perhaps your MP as well. Contact details for both follow below.

Tuesday 10 July 2012

Ten signs of trouble with the deprivation of liberty safeguards

(A pdf copy of this post is available here)

Recently I've been trying to encourage various organisations to pay attention to the problems with the deprivation of liberty safeguards. The Mental Health Alliance recently published a second review of the DoLS, confirming that there are serious problems with the safeguards. Drawing from their report, and my own research, here are ten reasons why organisations with an interest in human rights should be really worried about the DoLS:

Recently I've been trying to encourage various organisations to pay attention to the problems with the deprivation of liberty safeguards. The Mental Health Alliance recently published a second review of the DoLS, confirming that there are serious problems with the safeguards. Drawing from their report, and my own research, here are ten reasons why organisations with an interest in human rights should be really worried about the DoLS:

Monday 9 July 2012

Is there an ongoing lack of CQC inspections in residential care for adults with learning disabilities?

Back in 2004 the Commission for Social Care Inspection (CSCI) and the Healthcare Commission were tipped off by a local branch of Mencap that adults with learning disabilities were being abused in services run by Cornwall Partnership NHS Trust. The report that followed their joint inspection made headlines, a police investigation followed and documented horrific abuses - although in a decision that continues to puzzle abuse victims and their families, no prosecutions ever followed. Last year, abuse victims from Cornwall won a large payout from a civil claim, but as one carer told a local newspaper, 'the scars never go away'.

The Cornish scandal is often associated with assessment and treatment centres, but what is often forgotten is that the majority of victims were not in healthcare settings but in supported living services run by the health trust. Following the Cornwall scandal, the Healthcare Commission launched a nationwide audit of inpatient healthcare services, producing a hard hitting report entitled A Life Like No Other (2007). The report concluded that adults with learning disabilities in healthcare settings experienced highly restrictive and institutional regimes, had little support to maintain or build relationships, had few meaningful activities to occupy them, little access to advocacy services. The report concluded 'We cannot be sure that the human rights of people with learning difficulties are always upheld.' In the early days of the Care Quality Commission (CQC) a small sample of these healthcare services were revisited, and depressingly the report found that little had improved (2009).

The Cornish scandal is often associated with assessment and treatment centres, but what is often forgotten is that the majority of victims were not in healthcare settings but in supported living services run by the health trust. Following the Cornwall scandal, the Healthcare Commission launched a nationwide audit of inpatient healthcare services, producing a hard hitting report entitled A Life Like No Other (2007). The report concluded that adults with learning disabilities in healthcare settings experienced highly restrictive and institutional regimes, had little support to maintain or build relationships, had few meaningful activities to occupy them, little access to advocacy services. The report concluded 'We cannot be sure that the human rights of people with learning difficulties are always upheld.' In the early days of the Care Quality Commission (CQC) a small sample of these healthcare services were revisited, and depressingly the report found that little had improved (2009).

Thursday 5 July 2012

Deprivation of liberty and the struggle for meaning

The meanings of words are where battles are fought. Philosophers have known, since the linguistic turn, that meanings are slippery things - prone to evolution and change, impossible to exhaust, impossible to fix. And yet - so much rests on meanings, and nowhere is that more apparent than law. Several schools of discourse analysis are premised upon the idea that the use of language is a form of struggle. Writing in the twentieth century, Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin asked 'who owns meaning?' and concluded that we 'rent' meaning from the community, but that as members of that community we also shape it. Efforts to shape it can bring us into conflict, and efforts to use it carry the 'taste' of other meanings which we did not intend. Famously, Ludwig Wittgenstein decided that he hadn't, after all, solved all the problems of philosophy in his Tractatus, with a theory that the meanings of words correlated with what can be pictured in the world. In an even more inscrutable set of aphorisms (which he sent to his former tutor, Bertrand Russell, with a letter stating “Don't worry, I know you'll never understand it”) he concluded that meanings were not somehow given by the universe, logically dictated and lying in wait to be discovered. Meanings were simply how we used language to accomplish things, and as uses changed, so would meanings. An array of post-structuralist philosophers have argued that the way we use language and meanings are intrinsically linked to their socio-historical context, tied up with power and politics. Laclau and Mouffe, in their writings on discourse analysis, argue that we can understand political struggles by exploring struggles to fix meanings of key signifiers (words, phrases, symbols etc). One excellent example of recent times is the struggle to fix the meaning of marriage, with some of the churches contending that marriage can only mean a union between a man and a woman, and other groups wanting to use that term in a different way. To the churchmen, apparently, it is obvious that marriage can only mean this, but those schooled in the linguistic turn would point to the fundamental instability of meanings, their constantly changing and evolving use, and ask 'well why not?' They would understand this not as a debate on the internal logics of definitions but a wider struggle for meaning that brings significant material, social and political effects.

Tuesday 26 June 2012

The Local Government Ombudsman can investigate complaints about DoLS

A few weeks ago a comment on the blog raised the possibility that in some situations it might be more beneficial for those who had been subject to unlawful detention as a result of a breach of the deprivation of liberty safeguards (DoLS) to seek relief from the Local Government Ombudsman (LGO) than the Court of Protection. The commenter highlighted that:

'If you are lucky enough to get legal aid, you won't get to keep your damages unless you also get your costs paid by the wrongdoer, and that rarely happens in the COP because of the general rule and the fact that a DOLS breach is usually only one of various issues looked at in proceedings. And, even if you have got legal aid and it is worth pursuing, the courts can be very dismissive about asking for damages - often because it is said that there is no 'causation' - the person would have been in the care home even if the proper procedures had been followed - and because of the immense difficulty in showing that an earlier best interests decision was wrong, given how subjective such decisions are.'We've actually seen relatively few published judgments relating to breaches of the DoLS (Neary v London Borough of Hillingdon, 2011, of course being the most prominent example), but those cases are definitely out there. The interesting question is whether the Court of Protection is the only way to address these breaches of the DoLS, or whether the LGO could also offer some relief.

Friday 22 June 2012

Some thoughts on recent developments in right to die case law

A series of recent court cases have continued to explore the boundaries of our legal rights to determine how and when we die. The case of Tony Nicklinson raises important questions about the right of disabled adults to be supported by professionals in ending their life. By contrast, the case of 'E', an anorexia patient, shows that capacity is an important 'gatekeeper' concept for autonomy over end of life decisions. But E's case also raises questions about how 'best interests' decisions regarding end of life decisions should be made. The influence of 'intuition' on best interests decisions introduces problematic legal and political issues around uncertainty and arbitrariness. E's case also raises intriguing legal questions about the legal status of Court of Protection 'declarations' of best interests which are not accompanied by an order directing that a particular treatment be provided.

A what-I-missed-while-on-holiday roundup

Ten days without mobile phone reception or internet on honeymoon the West Highlands... My intention was to not even think about mental capacity whilst I was away, but unfortunately the novel I took with me had a subplot of unlawful deprivation of liberty in a nursing home and several interesting 'right to die' cases popped up in the news which I pondered whilst puffing up Munros. They concern, of course, the cases of Tony Nicklinson, and the recent Court of Protection case concerning the forced feeding of 'E', a young woman with anorexia nervosa, and I wrote about them here. This post, however, is a bit of a round-up of things I found in my inbox on my return.

In case you missed it, there's been a buzz about open justice this week, with Adam Wagner at the UK Human Rights Blog writing a great post on how the 'democratic deficit' in our courts isn't related to 'unelected judges' but about access to information. Adam argues:

...judges tend to come from the Bar. They are used to being a hired brain, squirreling away at clever written advice in the secluded surrounds of the Temple. That culture means that the courts resemble private members clubs rather than public fora where important decisions of social policy are being made every day.

This is no longer good enough. Judges and the Government fail to understand that in the internet age, open justice does not just mean opening the door to the courts. It means a completely new understanding of the old adage “Not only must Justice be done; it must also be seen to be done“.I agree! With rather good timing, the Centre for Law, Justice and Journalism at City University published their working papers from Justice Wide Open, an event earlier this year bringing together lawyers, judges, journalists and researchers to debate open justice in a digital age. Judith Townend, who organised the event, writes a summary of the topics covered on the Inforrm blog. There are papers by Geoffrey Robertson QC,the Master of the Rolls Lord Neuberger, Dr David Goldberg, Hugh Tomlinson QC, Emily Allbon, Nick Holmes, David Banisar, Heather Brooke, Mike Dodd, Adam Wagner, William Perrin, Professor Ian Cram, Dr Lawrence McNamara and yours truly.

Reports and resources

Various interesting reports, resources and articles found their way into my inbox whilst I was away, which might be of interest to others.

- The European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) has produced two interesting reports lately. One relates to involuntary detention in EU member states, and makes frequent reference to the possible impact of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities on detention under EU and Council of Europe law. Glancing over it briefly, I'm not sure it goes as far as some CRPD advocates might hope, but certainly it makes interesting reading and offers some comparisons between frameworks for involuntary placement in different EU states. The other report relates to the right to independent living for disabled people in the EU. The headline of these reports is 'Despite legislation, disability rights not realised in practice'. (H/T to @neilmcrowther for those reports, who contributed to the latter).

- The Mental Health Alliance have published a report reviewing the implementation of the Mental Health Act 2007. The report highlights several problems with the implementation of both the MHA and the deprivation of liberty safeguards, and is well worth a read.

- The Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities has published a paper by Romijn and Frederiks comparing the regulation of restraint in various different jurisdictions. It was prompted by the case of Brandon, which readers may remember was a young autistic teenager who was 'tethered' to a wall by an order of a judge in the Netherlands. The paper is interesting, although in my view doesn't quite distinguish carefully enough between law and guidance (at least in relation to the UK), and a few important areas of law are not discussed, but still interesting reading. (And paywalled reading, sorry about that...)

- And there are some interesting free webinars from Browne Jacobson legal training on DoLS and health and social care, available here, they are well worth watching. Particularly if, as has recently been reported, training on the deprivation of liberty safeguards is becoming 'unaffordable'... It is interesting to ponder how 'affordable' DoLS training might become if the chances of litigation for unlawful detention were higher. But unfortunately the chances of litigation are themselves contingent upon good training and good practice to support use of the safeguards and appeals mechanism, so unhappily there is no obvious source of pressure to remedy this situation. But I digress -watch the webinars!

Worcestershire County Council are consulting on a very concerning policy for capping maximum expenditure for adult social care at the rate of care home costs. In effect, unless other means of support can be found, where the costs of care in a person's own home cannot be met for less than the value of care in a residential home, then a person will either have to move into a care home (by consent or coercion, one presumes) or live with unmet care needs. My instinct is that if they get this through, then other local authorities may follow and we should be extremely concerned about what this will mean for rights to independent living, to family life and to the likelihood of using detention frameworks to coercive people into cheaper care home accommodation against their wishes. (not to mention fettering, etc etc). I can think of several local authorities who have (at least in the past, when I worked with them) operated informal policies of this nature - "oh no, if she needs more than 4 homecare visits a day it's off to a care home...." However, it's quite bold to see a council seeking to make it an explicit policy, and if offers an opportunity to explain how restricting community care expenditure in such a way can have such significant repercussions on the rights of older and disabled people and their families.

My gut instinct is the only people this policy will be financially advantageous to are the community care lawyers of Worcestershire; I can't imagine how a rash of DoLS appeals as people are coerced into care homes, or judicial reviews relying on Article 8, will help Worcestershire County Council's finances. I am working with the Spartacus Campaign to produce a response to this consultation, and we would be very interested to hear your views and any help campaigning against this policy that you can offer.

Thursday 31 May 2012

Who's talking about liberty?

Human rights organisations are rightly concerned about the civil liberties of protestors and those subject to control orders. Charities who promote the rights of disabled and older people are rightly concerned about their wellbeing in care services. But I'm troubled that few of these organisations seem to be kicking up a fuss about the liberty rights of adults in care services. Unlawful deprivation of liberty is an abuse in itself and a risk factor for situations like Winterbourne View. I'd like to call upon NGO's working to promote the human rights of older and disabled people to take a stand on the DoLS - people in care services have liberty rights, just like anybody else.Like liberty itself, deprivation of liberty comes in all kinds of shapes and sizes. There's the paradigm case of the prisoner, which we easily call to mind when we think of detention, and perhaps also certain forms of psychiatric detention. Then there are various 'borderline cases', which the courts have (broadly) held do not amount to detention, and yet many campaigners feel that they do - like control orders placed on terror suspects, kettling of protestors, and so on. In the human rights community there has been considerable focus on these particular borderline cases - but in my small corner of research I worry about another community, much larger than that affected directly by control orders, and affected for far longer than kettled protestors, that human rights groups have barely spoken about. There are many thousands of adults with mental disabilities, with conditions like dementia, who live under regimes easily as restrictive as control orders, many of whom who have no safeguards at all, or extremely weak safeguards. Occasionally these cases are so extreme - like Winterbourne View - they hit the headlines, and occasionally cases that might be more typical - like that of Steven Neary - spark interest in the media. But somehow these fall into a separate bracket than other liberty issues, they do not seem to spark the same concerns about the liberty rights of our fellow citizens and what their implications are for a democratic society. They continue to be talked about in social care circles, but in human rights circles they seem to have sunk without a trace.

I have enormous respect for human rights NGOs like Liberty and Justice. I am a paid up member of Liberty, and have been for years. I am a member of Justice's student human rights network. I have enormous respect for the other organisations I am about to talk about, which work in the field of disability rights or rights of older people. But for quite some time now I've been wondering - why are none of these NGO's with a high profile on liberty issues, on disability rights issues, talking seriously about liberty rights in care? Why are none of them kicking up an enormous stink about the catastrophe that is the deprivation of liberty safeguards (DoLS)? In fairness, and as I'll show in a bit below, some are making a few noises about the DOLS, but in comparison with other campaigns and rights-issues these groups campaign on, DoLS really just fade into the background. Yet anybody who is serious about liberty rights should be really concerned about DoLS.

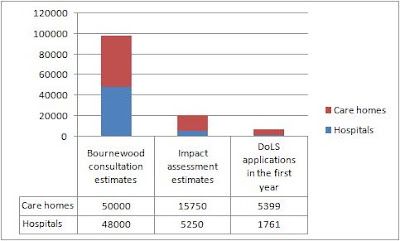

There are many tens of thousands of older people and people with dementia, with learning disabilities and other mental disorders who are subject to such severe restrictions on their liberty they mirror control orders, and will often constitute a deprivation of liberty. We know that a few thousand of these have the benefit of the DoLS, but it seems very likely that many are detained with no safeguards at all. The chart below shows early estimates, just after the ruling in HL v UK (2004) of how many people could require Article 5 safeguards in care homes and hospitals, it shows the estimate from the rather conservative impact assessment for the DoLS, and then it shows how many DoLS authorisations were issued in the first year. The numbers are rising, but very slowly, but note that the estimates on the chart count people whereas the DoLS data counts authorisations - and any individual may have multiple authorisations in a year. In short - it looks as if lots of people have slipped through the net.

The CQC have also said in the first and second reports on the DoLS, and in their Mental Health Act (MHA) visiting reports, that they have come across many examples of unlawful deprivation of liberty. Imagine if Her Majesty's Prison Inspectorate routinely found prisoners who hadn't been arrested or brought to court, imagine if the prisons had just banged them up without any authority. I think it would merit more than a a few comments in a report that only people working in the prison system read, it would be a national scandal. It seems possible that there are many thousands of people in care homes and hospitals today who are unlawfully deprived of their liberty. Imagine if thousands of people were subject to control orders, perhaps even tens of thousands - everybody would be talking about it. But on DoLS - virtual silence.

Furthermore, it seems likely to me and others that the DoLS are 'not fit for purpose', that even where the DoLS are applied they do not provide an Article 5 compliant legal framework for detention. There's the problems with the appeal process, perhaps best exemplified by the fact it took Steven Neary's father a year to get his son home from being unlawfully detained in a care home (here are some reasons why). Contrast this with the six months it took HL's carers to get him home using habeas corpus and consider - who, in public life, is asking whether this new framework that is meant to prevent Bournewood scenarios is functioning properly? Ponder this too: because no data is collected on the outcome of the appeals process, for all we know the DoLS have only ever released one person from detention (Steven Neary). One person. And nobody seems to be asking any questions about that. And what about the care services who have unlawfully detained people - have any of them been directly litigated? Is there actually any realistic source of pressure to comply with the DoLS?

And then there's the state of case law on the meaning of deprivation of liberty - who is speaking out about that? There's the Cheshire judgment, which finds that if somebody is subject to equivalent restrictions on their liberty to 'an adult of similar age with the same capabilities and affected by the same condition or suffering the same inherent mental and physical disabilities and limitations', then they are probably not deprived of their liberty. Imagine if we said of dangerous criminals that if they were held in circumstances comparable to other dangerous criminals they were not deprived of their liberty? Several eminent mental health and human rights lawyers have questioned whether the 'comparator' approach effectively discriminates against disabled people by setting the threshold of restrictions much higher for them before they are entitled to safeguards. But where are the disability rights organisations speaking out about this ruling? Several lawyers have also questioned whether Cheshire makes a nonsense of the DoLS, and perhaps even the Mental Health Act itself, because it is hard to say when a person could be said to be detained under those Acts. Or try this one for size - in C v Blackburn and Darwen Borough Council [2011] a man with learning disabilities was confined to a care home he did not want to live in, when he left the care home he had to be escorted at all times by staff, he had even hammered the door down trying to escape - but a court found that he was not deprived of his liberty. I find this judgment absolutely staggering, and I doubt many people in human rights circles would feel comfortable with it, or what its implications might be. Yet despite a few bloggers and lawyers writing in blogs and journals read by bloggers and lawyers, who is talking about it? Nobody. I'll say again, if these judgments were affecting any other group, I think there would be a national outcry.

To confirm my suspicion that nobody is really talking about DoLS, I did a bit of research using a very crude content analysis method. Basically, I did site searches on Google for various NGOs and Quangos to see how often their websites were using key terms which could indicate an interest in these liberty issues and DoLS. I put this in a google spreadsheet so you can look at the figures yourself. The results, to my mind, were quite interesting.

Let's start with mentions of the DoLS in contrast with mentions of other liberty limiting regimes like 'control orders' and the

Mental Health Act (MHA). For Liberty and Justice, there were 321 and 91 mentions of control orders, respectively, but literally not a single mention of 'deprivation of liberty safeguards' on their websites. They did mention the MHA a handful of times, indicating they are aware of and interested in liberty issues relating to mental health, but nothing like on the scale of control orders. The EHRC mentions DoLS 20 times on its website, which is good and they have done some great interventions in DoLS cases in court, but contrast this with 160 hits for the MHA and 24 hits for control orders. The CQC, as you'd hope, have hundreds of thousands of hits for DoLS on their website, as well as the MHA (unsurprisingly, no mention of control orders). But what about the NGO's involved in disability rights?

So, the disability NGOs are talking about DoLS more than the human rights NGOs, but not nearly as much as the MHA, and not as much as you might hope if potentially thousands of people with dementia, learning disabilities and other mental disorders are being unlawfully detained.

hits for DoLS hits for MHA Mencap 16 6 BILD 9 46 Alzheimer's Society 3 3 Dementia UK 3 6 Age UK 70 56 Mind 53 534 Disability Rights UK 0 6

It's not that these disability NGOs aren't talking about rights though. Most of them use the word 'rights' on their websites many hundreds, if not thousands of times. But they seem to be talking about different kinds of rights to liberty rights. I did a set of searches contrasting mentions of various 'rights' buzzwords: freedom, choice, liberty, dignity, detention, and plotted the results (as proportions, so usage of a word on a given website is compared against other words on that site - not other sites - as sites varied in size):

So the disability-oriented NGOs use the words 'choice' and 'dignity' far more than they use the word 'liberty', or words relating to liberty - like freedom or detention (nb: many mentions of 'freedom' turned out to relate to Freedom of Information, or bus passes). I've long felt that many organisations associated with disability and care issues are more comfortable with 'dignity' than 'liberty' rights. "Choice" is also a favoured word in social care circles, but - to my mind - it offers a rather weak form of liberty, as the 'choices' on offer still remain within the control of whoever is offering them. Choice can be very important, but although it is very central to market-thinking about care provision, choice is not liberty.

Contrast this with the pattern of buzzword use on human rights NGO's websites:

Immediately you can see that they're not so concerned with 'choice' or 'dignity', but liberty, freedom and detention feature highly (you would expect Liberty to talk about liberty a lot, but note that Justice does as well). So human rights NGOs seem to be much more oriented towards liberty rights than dignity rights, especially in comparison with disability NGOs. And finally, the CQC and the EHRC:

Both organisations mention detention a handful of times, although not as much as the human rights NGOs. But CQC places a lot more emphasis on dignity and choice and EHRC placing much more emphasis on freedom. If you see EHRC as being more of a 'human rights' organisation, and CQC as more of a disability/care oriented organisation, then that fits the pattern just described for the NGOs.

This content analysis is far from perfect - it relies upon a Google site search, it counts hits not usage of particular words, it ignores context, and also its slightly confounded by things like freedom bus passes. But I think it does suggest that although 'rights' discourses are pretty pervasive throughout these NGOs and Quangos, the kinds of rights different organisations and NGOs are interested in differ markedly. NGOs oriented towards civil rights and freedoms, in line with a more traditional liberty-oriented conception of human rights, are very deeply concerned with detention. But given their silence on DoLS, it would seem they are only interested in particular forms of detention - the unlawful detention of older people and people with disabilities seems to have passed them by. Meanwhile, the organisations who are intimately involved with working with people with dementia and learning disabilities, who conduct many important and laudable campaigns to improve conditions in care settings and life opportunities, seem to connect these issues far more with 'dignity' and 'choice', rather than liberty. Put bluntly, those oriented towards care don't care much about liberty; those oriented towards liberty don't care much about care. As a result, nobody who you might expect to give a damn about the problems with DoLS is really rocking the boat.

Its not that dignity rights have no value - cases like Price v UK and Bernard v London Borough of Enfield show that it can be very usefully deployed. But we should also bear in mind that in legal terms, dignity offers relatively weak protection, it certainly doesn't carry with it the well established case law, and procedural safeguards of Article 5. And dignity can also be deployed in ways that might be quite antithetical to liberty and self-determination. Elaine McDonald was told by the court that to use incontinence pads when continent was 'dignified', although she didn't experience it that way. In C v A Local Authority the staff's idea of 'dignity' was used to justify seclusion of a young man with learning disabilities in conditions which most of us would consider undignified to say the least. Cases like C v A Local Authority also show that dignity can be enhanced when liberty issues are taken seriously, because it requires independent scrutiny of restrictive practices. It will be interesting to see, when the Serious Case Review is published, whether the victims of abuse at Winterbourne View were subject to frameworks like DoLS which inject external scrutiny to the conditions of detention, and offer families opportunities to speak out about their concerns. My money is that they weren't, and I don't understand why so few organisations (rightly) shouting about Winterbourne View aren't raising this question. The question we've settled for is "where was the CQC?", forgetting "where were the best interests assessors, mental capacity assessors, Independent Mental Capacity Advocates and rights of appeal to the Court of Protection?" If detention under DoLS should be in a person's best interests, and if they should be supported and enabled to appeal against detention, why on earth weren't Winterbourne View patients all in the Court of Protection? Something has gone horribly wrong here, and voluntary and unenforceable dignity codes aren't going to fix it.